Opinion: The heart of scientific progress beats for all of us

I’m in my 80s now, so I remember what life was like in the 1940s and 1950s. In those days, heart attacks hung like the Sword of Damocles.

They took the lives of so many, and few knew what to do about it. Several times, neighbors called my dad, a neurosurgeon, to their houses, only for him to find someone dead in bed. At the news of the death of another friend, Joey, who died at age 39, my parents could only shake their heads.

Philanthropist Mary Lasker and U.S. Sen. Lister Hill of Alabama took the long view. Seeing the health problems that beset America but also seeing the beginnings of medical science progress, in 1955 they persuaded the federal government to vastly expand the National Institutes of Health, targeting research on heart disease, cancer and stroke, the major killers of Americans. Over the following decades, the NIH and other agencies have spent billions of dollars on in-house research and on grants to hospital and university researchers. Amazing progress has ensued, benefiting us all.

Here is one personal example. In early December, my next-door neighbor David Levine, a 71-year-old law professor in apparently good health, felt some discomfort in his upper back. He wisely visited his primary care doctor. Suspicious of a heart problem, she sent him to cardiac stress testing.

The stress testing was abnormal, which led to scheduling an angiogram promptly. As David nervously anticipated his angiogram, I reassured that this is now just routine, the welcome medical situation of “another one of these” rather than the dreaded, “Hmm, this is challenging.”

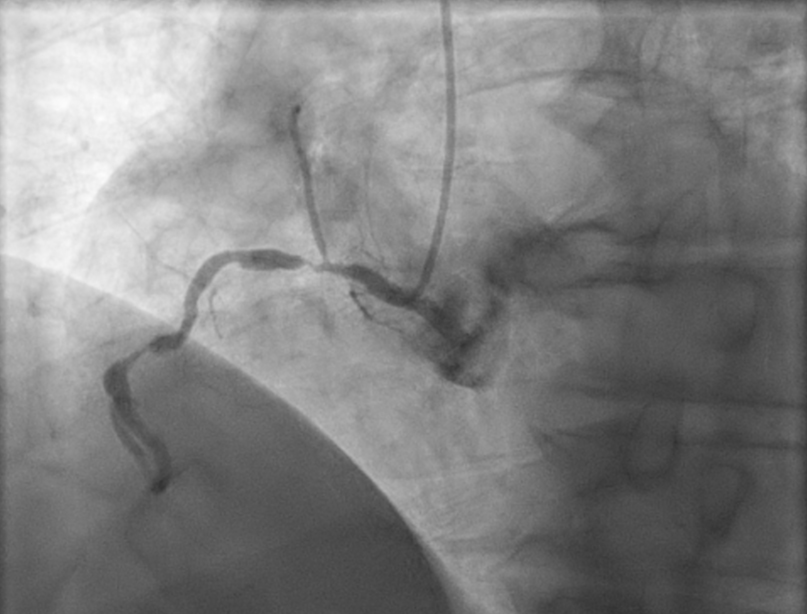

The angiogram would have seemed otherworldly to my parents’ generation. The cardiology team made a small puncture of David’s right radial artery and threaded a catheter up into his coronary arteries. They were surprised to find that the right anterior descending coronary artery was 90% blocked in two adjacent spots, a very dangerous condition.

They inserted stents and transformed the arteries from 90% blocked to 0% blocked in just a few minutes. David was under waking sedation for the 90-minute procedure, answering questions from the surgical team and watching continuous images of his beating heart on a monitor as they operated.

After the procedure, the interventional cardiologist told David he was only a few months from a heart attack — the 1950s scenario. Instead, just four hours later, David was on his way home to resume his family and professional life. We laughed together at the wonder of it all.

David’s story is repeated daily for people in every walk of life. Did Lasker and Hill dare to imagine this future? We must be grateful to them and to the researchers and practitioners who developed such techniques, the professionals who care for us, and to the leaders who continually invested on behalf of subsequent generations.

Related Articles

Opinion: What’s the truth about sobriety? Here’s my answer

Is bird flu the next pandemic? What to know after the first H5N1 death in the US

‘Obamacare’ hits record enrollment but an uncertain future awaits under Trump

San Francisco curbs syphilis rates with cheap ‘morning-after’ pill

Can probiotic supplements prevent hangovers?

Was it too expensive? We can ponder government spending priorities, but as Lasker said, “If you think research is expensive, try disease.” It takes money, time and patience, but look at the results for millions of people.

With a new presidential administration assuming power in Washington, we hope that they honor the vision of Lasker and Hill and keep investing in scientific progress. Let them not be seduced by the vision of headlines trumpeting mindless “efficiency” and claims of “money saved.”

Let’s hope we won’t be led by those who know the price of everything and the value of nothing. What could be of higher value, after all, than what we have just experienced?

Dr. Budd Shenkin is a physician in the East Bay and a graduate of the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley, where he is a member of the board of advisers.