Dense breasts can make it harder to spot cancer on a mammogram

By CARLA K. JOHNSON

When a woman has a mammogram, the most important finding is whether there’s any sign of breast cancer.

The second most important finding is whether her breasts are dense.

Since early September, a new U.S. rule requires mammography centers to inform women about their breast density — information that isn’t entirely new for some women because many states already had similar requirements.

Here’s what to know about why breast density is important.

Are dense breasts bad?

No, dense breasts are not bad. In fact, they’re quite normal. About 40% of women ages 40 and older have dense breasts.

Women of all shapes and sizes can have dense breasts. It has nothing to do with breast firmness. And it only matters in the world of breast cancer screening, said Dr. Ethan Cohen of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

With the new rule, “there are going to be a lot of questions to a lot of doctors and there’s going to be a lot of Googling, which is OK. But we want to make sure that people don’t panic,” Cohen said.

How is breast density determined?

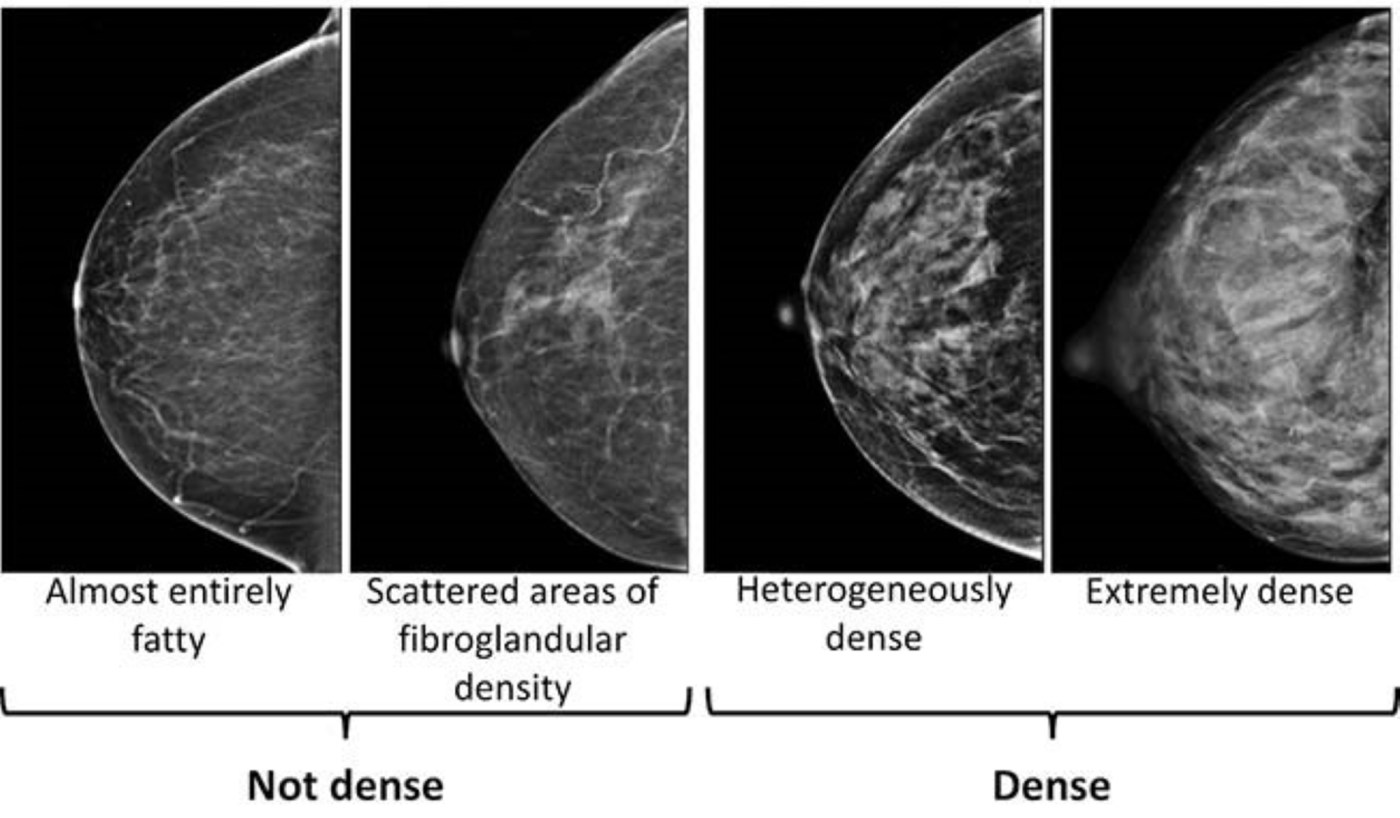

Doctors who review mammograms have a system for classifying breast density.

There are four categories. The least dense category means the breasts are almost all fatty tissue. The most dense category means the breasts are mostly glandular and fibrous tissue.

Breasts are considered dense in two of the four categories: “heterogeneously dense” or “extremely dense.” The other two categories are considered not dense.

Dr. Brian Dontchos of the Seattle-based Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center said the classification can vary depending on the doctor reading the mammogram “because it’s somewhat subjective.”

Why am I being told I have dense breasts?

Two reasons: For one, dense breasts make it more difficult to see cancer on an X-ray image, which is what a mammogram is.

“The dense tissue looks white on a mammogram and cancer also looks white on a mammogram,” said Dr. Wendie Berg of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and chief scientific adviser to DenseBreast-info.org. “It’s like trying to see a snowball in a blizzard.”

Second, women with dense breast tissue are at a slightly higher risk of developing breast cancer because cancers are more likely to arise in glandular and fibrous tissue.

Reassuringly, women with dense breasts are no more likely to die from breast cancer compared to other women.

What am I supposed to do?

If you find out you have dense breasts, talk to your doctor about your family history of breast cancer and whether you should have additional screening with ultrasound or MRI, said Dr. Georgia Spear of Endeavor Health/NorthShore University Health System in the Chicago area.

Related Articles

Flu shot may not be as effective as last year, but it’s still worth getting

Great balls of fire! Spicy-dish lawsuit by San Jose doctor against Los Gatos restaurant set for jury trial

A tale of two turfs: Bay Area residents split over using artificial grass

California neurosurgeon among four accused of $100 million insurance fraud scheme

What’s new and what to watch for in the upcoming ACA open enrollment period

Researchers are studying better ways to detect cancer in women with dense breasts. So far, there’s not enough evidence for a broad recommendation for additional screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force called for more research in this area when it updated its breast cancer screening recommendations earlier this year.

Do I still need a mammogram?

Yes, women with dense breasts should get regular mammograms, which is still the gold standard for finding cancer early. Age 40 is when mammograms should start for women, transgender men and nonbinary people at average risk.

“We don’t want to replace the mammogram,” Spear said. “We want to add to it by adding a specific other test.”

Will insurance cover additional screening?

For now, that depends on your insurance, although a bill has been introduced in Congress to require insurers to cover additional screening for women with dense breasts.

Additional screening can be expensive — from $250 to $1,000 out of pocket, so that’s a barrier for many women.

“Every woman should have equal opportunity to have their cancer found early when it’s easily treated,” Berg said. “That’s the bottom line.”